We’ve seen how images become matrices of numbers and how visual features can be learned hierarchically. But one question remains: what kind of neural network actually works well for images?

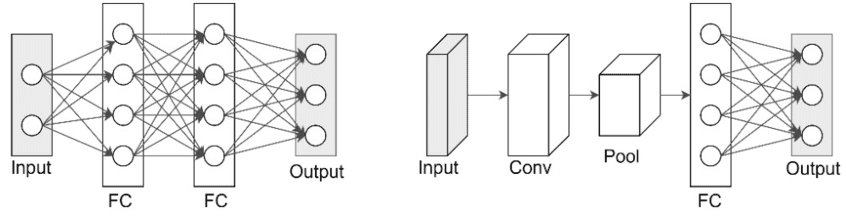

If we tried a regular feedforward network, each pixel of a color photo (about 150.000 inputs) would connect to every neuron in the first hidden layer. That means millions of parameters—expensive to train and blind to the fact that nearby pixels matter more than distant ones.

The breakthrough came with Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), which we've briefly covered in Chapter 4. Instead of treating every pixel independently, CNNs exploit two key truths: local patterns are meaningful and the same pattern can appear anywhere in the image.

This shift transformed computer vision and laid the foundation for nearly every modern image AI system.

Local Patterns and Shared Detectors

Visual features are local and repeat across the image. An edge, corner, or whisker looks the same in the top-left as in the bottom-right.

- In a fully connected network, one neuron might combine pixels from a cat’s eye, the sofa behind it, and the sky in the corner—nonsense for pattern recognition.

- CNNs instead connect neurons to small patches of pixels (like or ). This enforces spatial coherence: filters learn local features such as edges or textures.

Another trick: parameter sharing. The same filter scans across the entire image. A vertical-edge detector works no matter where the edge appears. This dramatically reduces parameters and ensures features are location-independent.

Convolution in Action

A filter (or kernel) is a small matrix of weights, take this compostion for example:

When "slid" across the image, this filter emphasizes pixels at the corners and center of each patch. Regions that match this arrangement produce strong activations, while areas without this structure return values close to zero.

🏞️ Convolution Sliding Example:

Each convolutional layer uses dozens—or hundreds—of filters, each detecting a different pattern (edges, curves, textures). The outputs form feature maps that show where those patterns appear.

Stacking layers builds a hierarchy:

- Early layers: edges, lines.

- Middle layers: corners, curves, textures.

- Deep layers: object parts (faces, wheels, leaves).

- Final layers: whole objects.

Through this layered process, convolutional networks gradually transform raw pixels into rich, high-level representations that enable accurate object recognition.

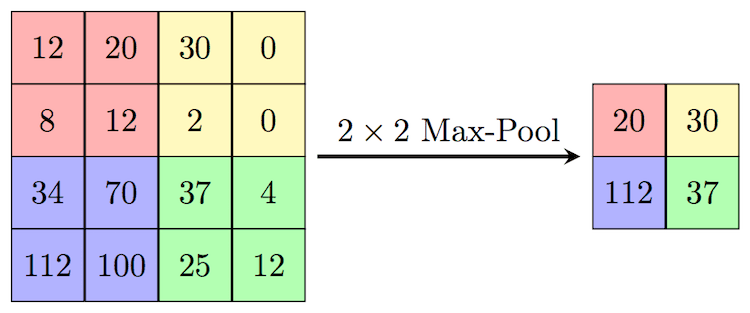

Pooling: Compact and Robust

After convolution, networks often apply a technique called pooling to reduce feature map size and gain robustness.

- Max pooling (most common): from each small patch (say ), keep the maximum value.

- This halves dimensions, reduces computation, and ensures small shifts in position don’t erase detection.

- A vertical edge nudged by one pixel still activates the same pooled region.

Pooling helps CNNs focus on what features are present, not exactly where.

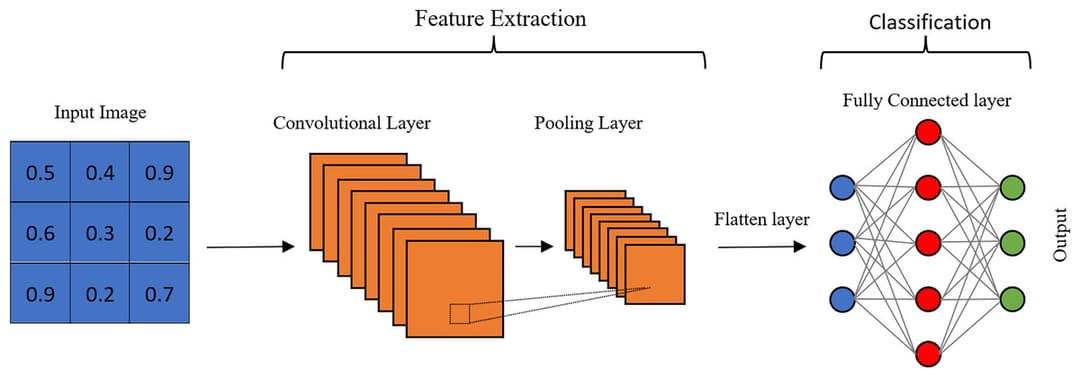

Building a CNN

A typical CNN architecture looks like this:

- Input: RGB image.

- Conv layer: filters detect edges → feature maps.

- Pooling: reduce size, keep strongest activations.

- More conv + pool layers: detect higher-level patterns.

- Flatten: turn maps into a 1D vector.

- Fully connected layers: combine features.

- Output: class probabilities (e.g. 10 categories for digits).

This builds the same architecture we encounterd earlier:

The deeper we go, the more abstract the features become—from pixels to parts to objects.

Training CNNs

CNNs train with backpropagation, just like other neural networks. The difference is that instead of learning arbitrary weights for every pixel, they learn the small set of filter values that best capture useful patterns. Just like other Deep Networks we explored in earlier chapters, CNNs follow a training loop:

- Start with random filters.

- Show thousands of labeled images.

- Compute predictions and errors.

- Backpropagate to adjust filter weights.

- Repeat until the filters detect meaningful features automatically.

Large datasets like ImageNet (millions of images across 1.000+ categories) enabled CNNs to learn general features transferable across tasks.

Why CNNs Work So Well

CNNs succeed because they align with how images work:

- They preserve spatial structure instead of flattening it.

- They learn hierarchies of features automatically.

- They use fewer parameters via weight sharing, making them efficient.

- They naturally handle translation invariance—a cat is a cat whether left or right.

- Pooling adds robustness to shifts, scale, and noise.

This synergy of design and data made CNNs the breakthrough architecture for vision.

Real-World CNN Applications

CNNs have revolutionized computer vision across numerous applications, often achieving superhuman performance on specific tasks.

🏞️ Image Classification: CNNs categorize images into thousands of classes, powering photo apps, content moderation, and visual search.

🏥 Medical Imaging: They detect cancers, fractures, and diseases in X-rays, MRIs, and CT scans—sometimes more reliably than humans.

🚗 Autonomous Vehicles: CNNs process camera feeds to read signs, spot pedestrians, and track vehicles in real time.

🏭 Manufacturing: Used for defect detection, assembly checks, and robotic guidance, CNNs catch flaws too subtle for human inspection.

Limitations and Challenges

Despite their success, CNNs face several important limitations that researchers continue to address.

- Heavy computation: training deep CNNs is expensive.

- Data hungry: require huge labeled datasets.

- Adversarial weakness: tiny perturbations can fool them.

- Domain sensitivity: a model trained on web photos may fail on medical scans.

- Bias: underrepresented groups or contexts in training data can lead to unfair outcomes.

These limitations drive newer architectures like Vision Transformers—but CNNs remain the foundation.

Final Takeaways

Convolutional Neural Networks changed the game by respecting what makes images unique: local patterns, spatial relationships, and repeating features.

By stacking convolution and pooling layers, CNNs automatically learn visual hierarchies—from edges to objects—without hand-crafted rules. They power applications across healthcare, cars, factories, and beyond.

While data needs, computational cost, and vulnerabilities remain challenges, CNNs provided the blueprint for modern computer vision and even inspired the architectures that now extend into image generation.