Before deep learning, computer vision began with a humbler goal: spotting patterns in raw pixels. Just as NLP once relied on bag-of-words (counting words without context), early vision systems depended on basic feature detection—edges, corners, and textures—that could be combined into crude visual descriptions.

The First Step: Edges

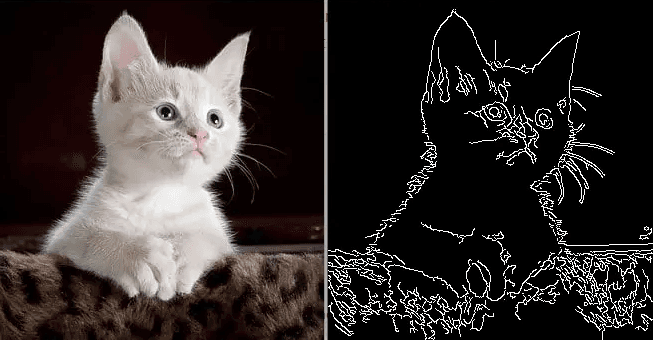

Edges mark the boundaries where pixel values change sharply—like the outline of a cat’s ears against a sofa. Detecting edges was one of the earliest breakthroughs in computer vision because it reduced the chaos of millions of pixels into something structured.

🏞️ Edge Detection Example An edge detector applies a filter that highlights sudden jumps in brightness. Horizontal filters pick out whiskers, vertical filters highlight stripes, diagonal filters trace ear outlines.

Algorithms like the Canny edge detector became classics in the 1980s, capable of producing surprisingly crisp outlines of objects. Even today, Canny edges are still used as quick preprocessing steps or visualization tools—proof that some of these early ideas remain relevant.

Corners, Textures, and Simple Features

Edges alone aren’t enough—you also need to know where they meet or repeat.

- Corners: where two edges intersect, marking key landmarks like the corner of an eye or the edge of a building.

- Textures: repeating patterns such as fur, brick walls, or grass.

- Gradients: smooth changes in brightness or color, hinting at shadows and depth.

A photo of a cat, reduced to these features, might read as: short thin lines (whiskers), fuzzy textures (fur), two circular patches (eyes).

It’s not recognition, but it’s a compressed description of what’s in the scene.

The Analogy to NLP

This stage of computer vision is much like bag-of-words in NLP:

- Bag-of-words: counts word occurrences but ignores grammar.

- Early vision: detects edges/textures but ignores global shape.

Both approaches capture local signals only. Just as bag-of-words can’t tell if “not bad” is positive, an edge map can’t tell a tiger from a striped sofa.

Building Blocks, Not Understanding

These detectors provided building blocks for more advanced algorithms:

- With edges, you could outline shapes.

- With corners, you could match keypoints across images (useful for stitching panoramas).

- With textures, you could characterize materials like wood, fabric, or stone.

But the systems were brittle. Change the angle, lighting, or background, and recognition often failed. A cat wasn’t “whiskers + fur + ears”—it was just a loose pile of patterns.

🦓 Zebra Example: Try showing a simple edge detector a zebra behind tall grass. The detector happily records “lots of stripes”—but it can’t tell if they belong to a zebra, the grass, or even a fence. Humans solve this effortlessly, but early systems couldn’t.

The Transition Point

Recognizing patterns was a necessary foundation. It proved that pixels could be transformed into useful signals and that local structure mattered. But like bag-of-words, it hit a ceiling: too brittle, too shallow, too handcrafted.

The next leap—automatic feature learning—would change everything. Instead of manually writing edge detectors, networks began to learn features themselves, stacking them into deeper, more abstract hierarchies. This shift mirrors how NLP moved from word counts to embeddings and neural models.

Final Takeaways

Early computer vision was about manually detecting simple patterns—edges, corners, textures—that turned raw pixels into signals. These features worked like the “words” of visual data, but they lacked the power to capture whole objects or meaning. They paved the way for CNNs, which could learn these patterns automatically and combine them into higher-level concepts. Recognizing patterns is the bridge between raw pixels and modern deep learning in vision.