When you look at a photo of a cat, you don’t consciously notice the thousands of details—fur texture, lighting, background—but your brain pieces them together instantly. Computers don’t have that luxury. For them, the same image is nothing more than a giant spreadsheet of numbers: millions of tiny colored dots called pixels.

There are no "cats" or "whiskers" in this representation—just patterns of brightness and color. Computer vision is the field that tackles this problem: how to turn raw pixels into understanding. It’s the bridge between numbers and visual concepts, from detecting tumors in scans to powering self-driving cars.

What Computers Actually "See"

Digital images are nothing magical—they’re just matrices of numbers. We've already covered this way back in Chapter 2, but let's refresh the idea for a moment:

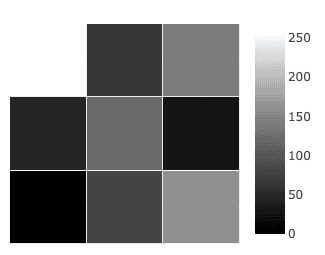

- A grayscale photo is a grid where each cell stores brightness: 0 for black, 255 for white, and values in between for shades of gray.

- A color photo stacks three matrices—red, green, and blue (RGB). Each pixel is a triple like for purple.

Together, all pixels make an image:

A smartphone photo might have 12 million pixels each with three values. That’s 36 million numbers for a single picture. Somehow, from this sea of numbers, computers need to find patterns that correspond to “cat”, “car”, or “traffic light”.

Why Vision is Hard

Turning numbers into objects is far more challenging than it sounds. A single object—say, a cat—can appear in endless ways:

- Variation: Different lighting, angles, and distances completely change pixel values.

- Occlusion: Objects are often partially hidden, like a cat peeking behind a sofa.

- Context: The same pattern might mean different things—a striped patch could be a tiger, a basketball, or a warning sign.

- Scale: An object might fill the whole frame or be a tiny dot.

Humans handle these effortlessly because our brains are wired for invariance. For machines, these become core challenges:

- A cat rotated sideways is still a cat.

- A cat in the corner should be recognized the same as one in the center.

- A cat in daylight and in shadow remains the same object.

Computer vision models must learn these invariances to function in the real world.

From Raw Pixels to Features

Early vision systems tried hand-crafted rules like: “look for two triangles above two circles to find a cat’s face.” This broke down quickly—too much variation, too many exceptions.

The breakthrough was to let systems learn features automatically through machine learning, building them in layers:

- Low-level: edges, corners, textures, simple gradients.

- Mid-level: curves, object parts (eyes, wheels, leaves).

- High-level: whole objects (cats, cars, trees).

📸 Canny Edge Example: An early example is the Canny Edge Detector, which identifies edges by analyzing pixel intensities and using derivatives to detect sudden changes in value (just as derivatives measure change):

This layered learning mirrors how our visual cortex works—detecting edges first, then shapes, then whole scenes.

Preprocessing the Image

Before features can be learned, images are usually standardized.

- Normalization: Pixel values are scaled (e.g. 0–1) to make training stable.

- Resizing: Different photos are resized (say, ) so the network has consistent input.

- Data augmentation: Training images are slightly rotated, flipped, brightened, or blurred—teaching the model that these variations don’t change identity.

- Color spaces: Sometimes images are converted from RGB to HSV, separating brightness from color, which helps with lighting changes.

These steps make vision models more robust, teaching them that a slightly brighter or flipped cat is still a cat.

Ties to Earlier Concepts

Computer vision may seem new, but it builds directly on what you’ve already seen:

- Matrices & linear algebra: images are grids of numbers, and filters are just matrix operations.

- Pattern recognition: we’re looking for patterns in pixels, not in words.

- Feature learning: just as embeddings captured semantic similarity in NLP, learned visual features capture appearance similarity.

In short, the same math underpins both vision and language—only the data differs.

Real-World Applications

Computer vision has transformed numerous industries by enabling automated analysis of visual information at scales impossible for human processing.

🩻 Medical Imaging: AI systems scan X-rays or MRIs and highlight suspicious regions, like tiny fractures or early tumors, acting as an extra pair of eyes for doctors.

🚗 Self-Driving Cars: Cameras feed images into vision models that detect road signs, lane markings, pedestrians, and other vehicles, helping the car “see” its environment in real time.

🏭 Manufacturing Quality Control: High-speed cameras on assembly lines check products for flaws smaller than the human eye could spot, ensuring precision at scale.

🕵️ Security and Surveillance: Vision systems analyze video feeds to detect unusual activity, recognize faces, or estimate crowd sizes in busy areas.

These applications illustrate how computer vision extends human perception, unlocking new possibilities across science, industry, and everyday life.

The Limitations and Challenges

Despite progress, computer vision isn’t foolproof. There are still numerous problems to tackle:

- Tiny pixel changes (imperceptible to humans) can fool systems—turning a stop sign into a “yield” sign.

- Models often fail outside their training domain (e.g. trained on stock photos, but tested on blurry CCTV).

- They recognize patterns but don’t “understand” them—a cat is an object, not a living creature needing care.

- Bias creeps in if training data underrepresents certain people or contexts.

- Real-time vision (like in self-driving cars) requires immense computing power.

These highlight the gap between recognition (spotting patterns) and understanding (grasping meaning).

Looking Forward

The frontier of vision AI is moving from “what is in the picture?” to “what does it mean?”

- Models now describe images in words or answer questions about them.

- Vision is being combined with language in multimodal models that understand both text and pictures.

- The same principles are being flipped: instead of recognizing objects, models now generate new images from text prompts.

This opens the door to AI that doesn’t just see but also creates—a topic we’ll dive into in the next chapter.

Final Takeaways

Computer vision starts with simple numbers—pixel grids—but builds upward through learned features to recognize objects and scenes. The challenges of variation, occlusion, and scale make vision difficult, but techniques like preprocessing, feature learning, and invariance handling make it possible.

Today, computer vision powers applications from healthcare to self-driving cars, while also facing challenges of robustness, bias, and true understanding. The next leap is multimodal AI, where machines both see and create, bringing us closer to human-like perception.