Once features can be extracted—whether by handcrafted filters or learned automatically with CNNs—the next natural step is classification: deciding what an image contains.

When you upload a photo and your phone suggests “dog”, “beach”, or “birthday”, that’s classification at work. At its simplest, classification means taking the compressed, learned representation of an image and assigning it to one or more categories.

But computer vision doesn’t stop at classifying whole images. Modern systems detect multiple objects, segment precise regions, and even generate natural language descriptions. Classification is just the entry point into richer visual understanding.

The Basics: Image Classification

The simplest setup is single-label classification: each image belongs to exactly one category.

- A digit image: “3” not “7”.

- A medical scan: “tumor” or “healthy”.

- A wildlife photo: “elephant” not “rhino”.

The pipeline looks familiar by now:

- Input: Image → pixel matrix.

- Feature extraction: CNN layers learn edges, textures, shapes.

- Representation: Flattened feature vector.

- Classifier: Fully connected layers + activation function → probability distribution over classes.

Just like in NLP prediction, we are working with probabilities again! The model doesn’t say “100% cat”, it outputs something like this:

Going Further: Beyond Simple Labels

Most real-world images contain more than one object. Classification alone can’t tell you where things are or how they interact. This led to new tasks that extend the same principles.

Multi-Label Classification: An image can belong to multiple categories simultaneously. A beach selfie might be tagged as person + ocean + sunglasses.

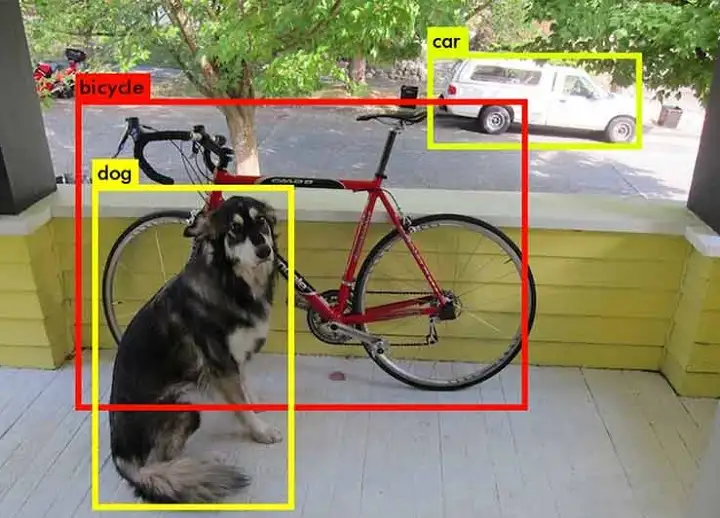

Object Detection: Detects and localizes multiple objects, drawing bounding boxes around each:

- “Dog” →

- “Bicycle” →

The model's output might look something like this:

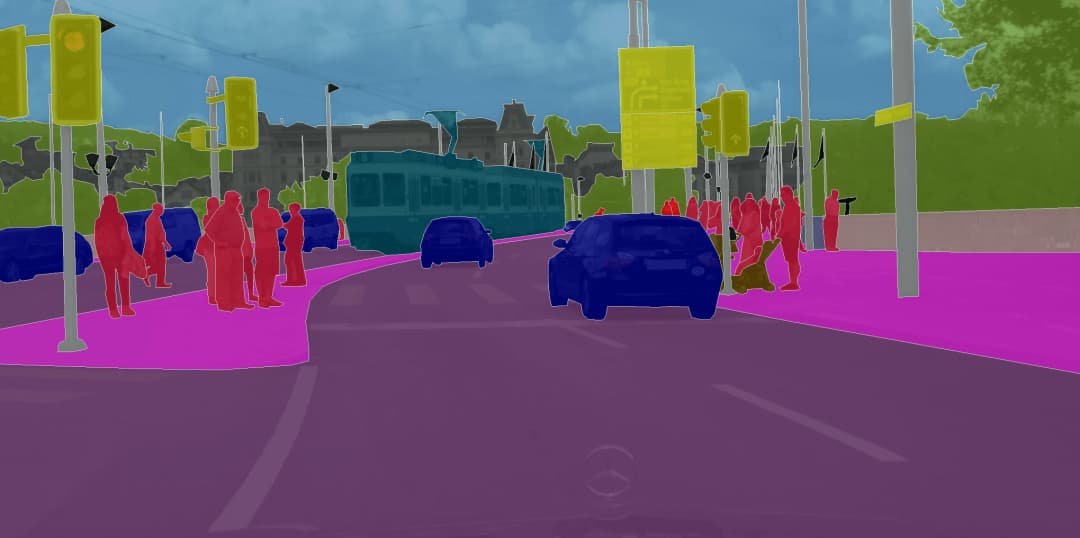

Semantic Segmentation: Goes pixel-by-pixel, labeling each pixel as “road”, “car”, or “sky”. This is crucial for self-driving cars that need to know exactly which pixels belong to pedestrians versus asphalt.

Instance Segmentation: A step further—distinguishing individual objects of the same type. Not just “three people” but “Person 1, Person 2, Person 3”, each with its own mask.

Scene Understanding: Looking beyond objects to context. Is this a “kitchen”, “forest”, or “highway”? Scene classification helps systems reason about where they are, not just what they see.

Real-World Applications

Classification and its extensions power many of today’s most visible computer vision systems.

🏥 Medical diagnosis: Classify chest X-rays as pneumonia vs. clear lungs, or skin images as benign vs. malignant.

🚗 Autonomous vehicles: Detect pedestrians, classify traffic lights, segment lanes. This is an example of semantic segmentation:

📱 Social media: Automatically tag faces, recognize objects for search (“show me all photos with bikes”).

🌳 Environmental monitoring: Classify satellite imagery for deforestation, crop health, or disaster damage.

The Challenge of Fine-Grained Classification

Not all classification is straightforward. Some tasks require distinguishing between categories that look extremely similar:

- Bird species that differ by a tiny stripe on the wing.

- Car models from the same manufacturer, year, and color.

- Medical images with subtle pathological signs.

These fine-grained tasks push vision systems to learn very precise features and often require expert-labeled data.

🩻 Medical Detection Example: For doctors, telling apart two skin conditions might hinge on texture differences invisible to laypeople. CNNs can be trained to detect these subtle variations—but only if they’re shown enough carefully annotated cases.

Classification in Context

One limitation of traditional classification is that it often ignores context.

- A lone baseball bat might be classified as “stick”. But put it next to a glove and field, and the system recognizes “baseball.”

- A round orange shape could be a basketball or an orange fruit—the surrounding pixels decide.

This is where newer architectures (like attention mechanisms and transformers, which we’ll explore later) help models consider relationships across the entire scene.

From Classification to Generation

The leap from recognizing “what is there” to “imagining what could be” comes from the same roots. Models that learn rich visual representations for classification can reuse those features for generating images.

- A classifier trained to recognize cats has filters for whiskers, fur, ears.

- A generator can reuse those features to construct a cat image from scratch.

Classification, in this sense, laid the foundation for modern generative vision models—the same way text classification fed into large language models.

Final Takeaways

Image classification is the gateway task of computer vision. Starting with whole-image categories, it naturally extended to object detection, segmentation, and scene understanding—tasks that bring AI perception closer to human-like vision. These systems already drive real-world impact in medicine, transportation, retail, and environmental monitoring.

But classification is not the end of vision. It’s the bridge: from local patterns to full-scene understanding, and from recognition to generation. The same features that power accurate classifiers also underpin the generative models that now create entirely new images.