At the core of every language AI system—whether it’s your phone’s autocomplete or ChatGPT—lies a simple idea: predict the next word. This task, called language modeling, is what allows machines to move from processing text to generating it—writing stories, answering questions, or holding conversations.

If an AI can reliably guess the next word in a sentence, it must have learned something about grammar, vocabulary, context, and even real-world knowledge. What started as simple pattern matching has grown into the foundation of today’s most advanced AI systems.

Predicting What Comes Next

Language modeling is about probabilities: given some words, which word is most likely to follow? This idea follows from other concepts that rely on probability, like picking a colored ball from a set of balls. We've learned about probabilities back in Chapter 2 and now we can put them to use!

Take the phrase: “The cat sat on the ___” . A good model ranks “mat” higher than “elephant", but also allows for “sofa”, “roof”, or “keyboard”, depending on context. To make such predictions, the model must understand:

- Grammar: “the” is often followed by a noun or adjective.

- Meaning: cats usually sit on solid objects.

- World knowledge: cats and furniture often appear together.

- Context: outdoor vs. indoor changes what fits best.

This simple guessing game captures the essence of how machines learn language. But how can we reliably predict there next words?

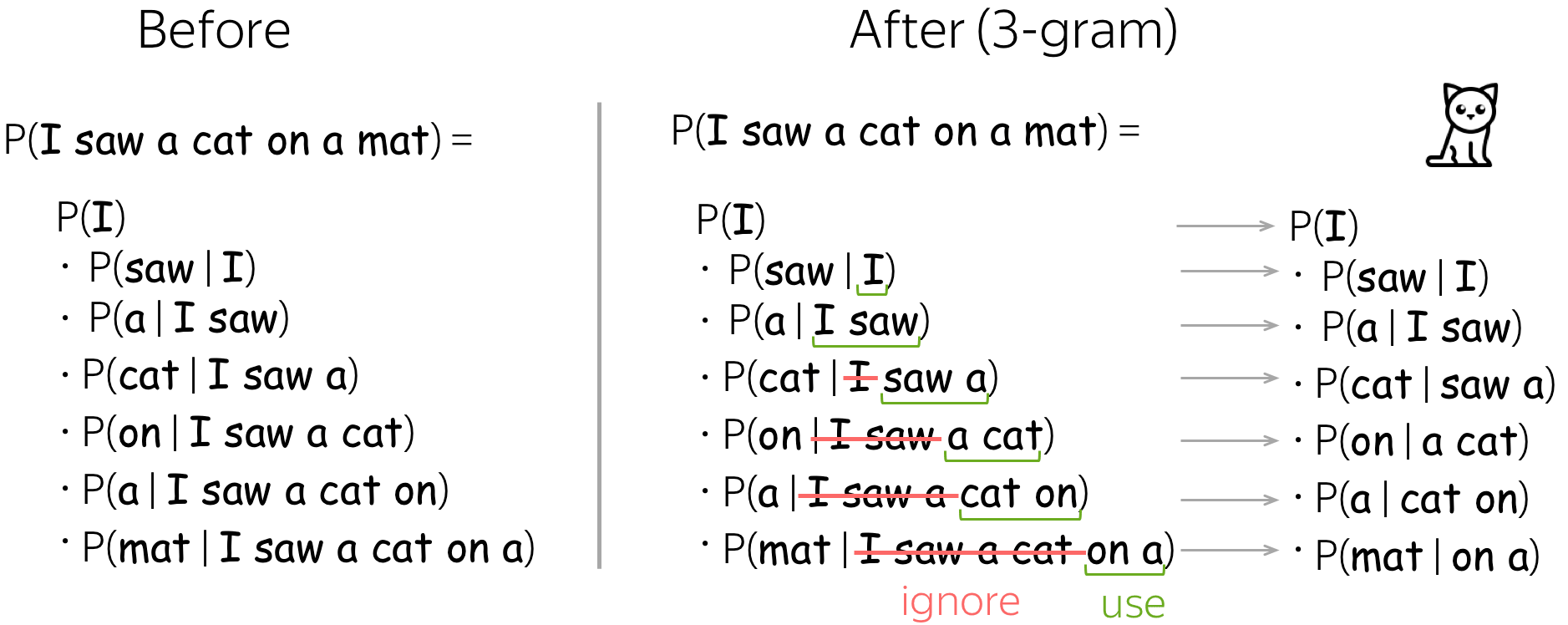

N-grams: The First Step

Before modern neural networks, early language models relied on n-grams—simple statistics about short word sequences. The idea is straightforward: the more often a word follows another in training text, the more likely it should be predicted.

- A bigram model (n=2) predicts the next word using just the previous one. If “the” is followed by “cat” 1000 times and “dog” 500 times, the model assigns a higher probability to “cat” after “the”.

- A trigram model (n=3) looks at two words back. After “the cat”, it might strongly predict “sat”, since that phrase appears often in training data.

- Higher-order models (4-gram, 5-gram, etc.) can consider more history but become harder to manage.

The result might look something like this:

Here's how they’re trained:

- Collect a large text dataset.

- Break it into n-grams (sequences of n words).

- Count how often each sequence occurs.

- Convert counts into probabilities for prediction.

N-grams sound good but they have some important limitations:

- Short memory: N-grams only look back a few words. They can’t capture long-distance relationships, like linking a subject at the start of a paragraph to a verb much later.

- Data sparsity: The number of possible sequences grows rapidly with n. Most longer word combinations never appear in training, so the model struggles with unseen phrases.

- Inefficiency: Storing counts for millions of n-grams requires huge amounts of memory, especially when most combinations are rare.

N-grams were an important first step: they showed that statistics could model language in a useful way. But their limitations pushed researchers toward more flexible methods—eventually leading to neural language models.

Neural Language Models

To overcome the limits of n-grams, researchers turned to neural networks. Instead of just counting how often words appear together, these models represent words as embeddings (vectors that capture meaning) and feed them into a network that learns broader patterns.

This allows the model to generalize beyond exact matches. For example, if it has seen:

- “The dog ran quickly”

- “The cat walked slowly”

…it can still make a good guess for “The rabbit moved ___” even if that sentence never appeared in training. The model recognizes the similarity between “dog”, “cat”, and “rabbit”, as well as between “ran”, “walked”, and “moved”.

Another breakthrough is longer memory. While n-grams could only look back a few words, neural models can consider dozens, hundreds, or even thousands of words. This makes it possible to stay consistent across paragraphs, keep track of topics in essays, or maintain characters in a story.

In short, neural language models don’t just memorize sequences—they build flexible representations that let them handle new combinations and longer contexts.

From Prediction to Capabilities

What’s remarkable is what happens when these models scale up—trained on massive text collections with bigger networks. Out of the simple next-word prediction task, unexpected capabilities emerge.

- Answering questions: A model trained to complete “The capital of France is ___” with “Paris” eventually learns to answer a wide variety of factual questions, even if phrased differently.

- Translation: By seeing multilingual texts side by side, models pick up how words in one language map to another, without ever being explicitly taught.

- Math and logic: When exposed to mathematical expressions in text, models learn that and extend that to other arithmetic problems. They aren’t doing math like a calculator, but recognizing and continuing patterns.

- Programming: Trained on code repositories, models learn to autocomplete functions, fix syntax errors, or even write new code.

- Common sense: By absorbing everyday language, models infer patterns like “ice is cold” or “people need food.” These aren’t facts stored in a database—they’re statistical regularities captured from text.

Crucially, none of these abilities were directly programmed in. They emerged naturally because predicting the next word at scale forces the model to capture grammar, meaning, and knowledge about the world. This was the moment language models shifted from simple text predictors to systems that appear capable of reasoning, recalling facts, and generating useful answers.

The Scale Revolution

One of the biggest discoveries in AI is that language models get better simply by scaling up. When models grow in size, are trained on more data, and use more computational power, their abilities improve in a surprisingly smooth and predictable way.

- Early neural models in the 2010s had only a few million parameters—enough to capture local patterns but limited in scope.

- GPT-1 (2018): 117 million parameters, showing that large-scale training could produce coherent text.

- GPT-2 (2019): 1.5 billion parameters, with outputs that began to look genuinely human-like.

- GPT-3 (2020): 175 billion parameters, able to generate essays, code, and conversations that surprised even researchers.

- Modern frontier models now reach hundreds of billions to trillions of parameters.

Equally important is the training data. Early models were trained on curated collections like news articles or Wikipedia. Today’s large models learn from enormous slices of the internet—books, scientific papers, websites, forums, and more. This diversity exposes them to almost every topic humans write about, from cooking recipes to quantum physics.

The combination of size, data, and compute has transformed language modeling from a simple autocomplete tool into systems capable of long, coherent conversations, problem-solving, and creative tasks. This progression is often called the scaling revolution, because it shows that increasing scale alone can unlock new, unexpected capabilities.

Conversation and Beyond

At its core, even ChatGPT is still “just” a language model predicting the next word. What makes it feel conversational is the fine-tuning process: after being trained on internet-scale text, the model is further trained on dialogue examples and human feedback. This nudges it to generate responses that are not only grammatical but also helpful, polite, and coherent in conversation. This explains both its strengths and its limits:

- Strengths: ChatGPT can explain concepts, write stories, or answer questions in a natural, conversational way. It adapts tone and style depending on how you phrase your prompt.

- Limitations: It doesn’t “know” facts the way humans do. It’s not looking up information in real time but predicting text based on patterns in its training data. This means it can produce convincing but outdated or incorrect answers.

More modern language models are extended into the products we use today:

- Multimodal models: Models that combine text with images, audio, or video. For example, a model could describe what’s in a picture, generate an image from a text prompt, or even engage in spoken dialogue.

- Tool use: Some models are being taught to call external tools—like using a calculator for math, a search engine for up-to-date information, or a database for precise facts. This helps overcome the limits of prediction alone.

Together, these advances mark the shift from pure text prediction to AI systems that interact with the world in richer, more reliable, and more versatile ways.

Final Takeaways

Language modeling—predicting the next word—remains the foundation of AI systems. From early n-gram counting to massive neural networks, this task has proven powerful enough to unlock grammar, meaning, knowledge, and even reasoning-like abilities.

Modern models show that by learning to predict human text at scale, machines can generate responses that feel intelligent—even though at their core, they’re still playing the world’s most sophisticated guessing game.