Giving each word a simple ID number, like “cat" = 4, doesn’t tell us anything about meaning. “Cat” (4) looks just as close to “car” (6) as to "dog” (5), even though in reality cats and dogs are much more related.

Word embeddings fix this. Instead of single numbers, they represent words as vectors—lists of numbers—so that words with similar meanings end up close together in a mathematical space (but you know this from Chapter 2!). This simple shift unlocked modern language AI.

From Single Numbers to Vector Representations

Instead of representing "cat" as just the number 4, imagine representing it as a vector like:

This vector might have 100, 300, or even 1000 dimensions, where each dimension captures some aspect of the word's meaning.

The exact meaning of each dimension isn't always clear to humans, but the overall pattern captures semantic properties. The key insight is that words with similar meanings end up with similar vectors.

Consider how we might represent a few related words:

- "cat" → .

- "dog" → .

- "kitten" → .

- "car" → .

Notice how "cat", "dog", and "kitten" have similar values in many dimensions, while "car" has very different values. This mathematical similarity reflects semantic similarity.

Word2Vec: Learning Relationships from Context

The most famous method for learning embeddings is Word2Vec, developed at Google. Its core idea: you know a word by the company it keeps.

The model trains on text by predicting a word from its surrounding context, or the context given a word.

🦾 Training Process Example: Consider the sentence "The fluffy cat sat on the mat". The Word2Vec algorithm might learn by trying to predict "cat" given the surrounding words , or predict the surrounding words given "cat". Through millions of such examples, the network learns that words appearing in similar contexts should have similar representations.

During training on massive text corpora, the algorithm encounters patterns like:

- "The fluffy cat..." and "The fluffy dog..." (cats and dogs appear in similar contexts).

- "...ran quickly" and "...walked slowly"* (movement verbs share contexts).

- "Paris, France" and "London, England" (cities and countries show up together).

These contextual patterns get encoded into the vector representations, so semantically similar words end up mathematically close in the embedding space.

The Geometry of Meaning

Once we have word embeddings, we can use mathematical operations to explore semantic relationships. The distance between vectors reflects semantic similarity—closer vectors represent more similar words.

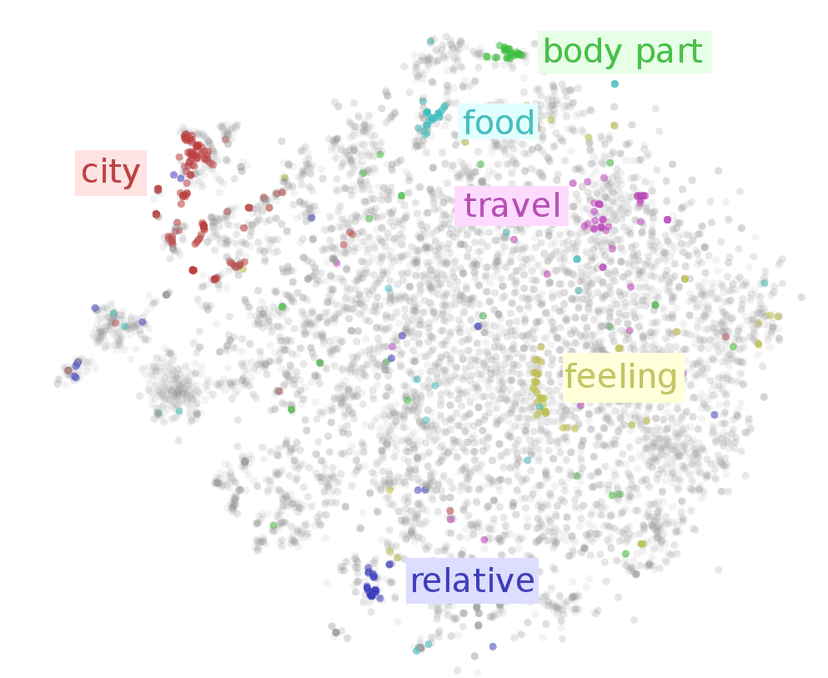

Just like clustering back in the shopping behavior example in Chapter 3, animals group together, emotions cluster near each other, countries form their own region, and verbs collect in another area. Take a look at some word clusters in embedding space:

This clustering happens automatically—we never told the algorithm that "cat" and "dog" are both animals, or that "happy" and "joyful" are both emotions. The algorithm discovered these relationships from observing which words appear in similar contexts across millions of sentences, so this is an example of unsupervised learning!

Vector Arithmetic: The Magic of Word Math

Perhaps the most fascinating property of word embeddings is that meaningful arithmetic operations work in the vector space. One famous example is: king - man + woman ≈ queen.

This works because the embeddings capture relational patterns. The vector difference between "king" and "man" represents something like "royalty" or "monarchical role". When we add "woman" to this difference, we get a vector close to "queen"—the female equivalent of a king.

More Examples of Word Arithmetic:

- Paris - France + Italy ≈ Rome (capital cities).

- Walking - Walk + Swim ≈ Swimming (verb forms).

- Bigger - Big + Small ≈ Smaller (comparative forms).

- Apple - Fruit + Vegetable ≈ Carrot (category relationships).

These relationships emerge naturally from the training process. The algorithm never explicitly learns that Paris is to France as Rome is to Italy, but by seeing these words in similar contexts across many documents, it encodes these analogical relationships into the mathematical structure of the embeddings.

Beyond Individual Words

Modern embeddings capture even more sophisticated relationships than simple word similarities and analogies. They encode cultural associations, temporal relationships, and even subtle biases present in the training data.

Cultural and Contextual Associations: Words associated with certain professions, activities, or concepts cluster together in ways that reflect real-world associations. "Doctor" might be closer to "hospital" and "surgery", while "teacher" clusters near "classroom" and "students".

Handling Multiple Meanings: Advanced embedding methods can even handle words with multiple meanings. The word "bank" might have different representations depending on whether it appears in financial contexts ("money", "loan", "account") or geographical contexts ("river", "shore", "water").

Temporal and Stylistic Variations: Embeddings trained on different time periods or text sources capture how language evolves and varies. Words might have different associations in 19th-century literature versus modern social media posts.

Training Your Own Embeddings

While pre-trained embeddings like Word2Vec, GloVe, or FastText work well for many applications, sometimes you need embeddings trained on specific domain text.

The Training Process:

- Collect a large corpus of text from your domain.

- Preprocess and tokenize the text.

- Train the embedding model using algorithms like Word2Vec or GloVe.

- Evaluate the resulting embeddings for quality and relevance.

- Fine-tune parameters if necessary.

Domain-Specific Benefits: Medical embeddings trained on medical literature will understand that "myocardial infarction" and "heart attack" are synonymous, while general embeddings might miss this connection. Legal embeddings understand relationships between legal terms that general embeddings don't capture.

Limitations and Challenges

Despite their power, word embeddings come with important drawbacks.

Static meaning: Classic embeddings give each word a single vector. “Bank” has the same representation whether it refers to money or a river, making it hard to capture nuanced context.

Bias: Because embeddings learn from human text, they also pick up human stereotypes—like associating “doctor” more with men than women. These biases can resurface in AI systems that use them.

Coverage gaps: Words missing from the training data—new slang, rare technical terms, or unique names—can’t be represented well.

Resource demands: Training embeddings requires large datasets and significant compute. Storing millions of high-dimensional vectors also consumes substantial memory.

The Foundation for Modern NLP

Word embeddings were a turning point in natural language processing. For the first time, computers could represent words in a way that reflected meaning rather than just labels. This shift unlocked everything from simple text classification to the large language models we use today.

The key idea is simple but powerful: patterns in how words appear together carry information about their meaning. Embeddings captured this mathematically, paving the way for more advanced systems. Modern models now use contextual embeddings that adapt word meaning to the surrounding text, but they still build on the same principle: semantic relationships can be learned from data and represented as vectors.

Final Takeaways

Embeddings transform words from arbitrary IDs into vectors where distance reflects meaning. By training on context, methods like Word2Vec discovered that related words cluster together and even support analogies through vector arithmetic.

While limited—static embeddings can’t adapt to context and may inherit bias—they provided the first real bridge between raw text and mathematical structure. This insight laid the groundwork for today’s AI, showing that meaning can be encoded in numbers and manipulated to perform tasks like translation, summarization, and question answering.