Everything we’ve covered so far—turning words into numbers, embeddings, context, and prediction—culminates in large language models (LLMs). These are the engines behind ChatGPT, Claude, and other conversational systems that can write essays, answer questions, and hold surprisingly natural dialogues.

The principle hasn’t changed: they still predict the next word. What’s different is scale. With billions of parameters, internet-scale datasets, and enormous computing power, the same basic recipe suddenly produces qualitatively new capabilities. Scaling up doesn’t just make predictions better—it unlocks skills like reasoning, coding, and creative writing.

Word Prediction in Action

At the heart of every large language model is still the same task: predicting the next word using probabilities. Given a sequence like “The capital of France is ___” the model calculates which words are most likely to follow, and picks the next word based on those probabilities.

This simple mechanism—probability-based word prediction—is what we explored in earlier chapters. What makes large language models remarkable is what happens when you scale this mechanism up with billions of parameters and internet-scale data.

From Language Models to Large Language Models

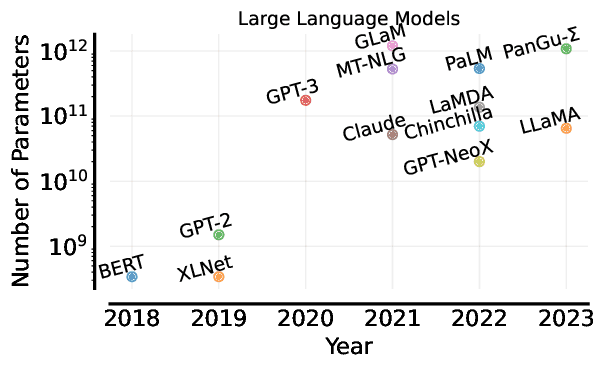

The shift from early models to LLMs is one of the most dramatic scaling experiments in AI history. The fundamental task—predicting the next word—remains the same, but three things grew by orders of magnitude:

- Model size: from millions to hundreds of billions of parameters.

- Training data: from curated corpora to vast swaths of the internet.

- Computation: training runs that require thousands of processors for weeks.

This growth follows what researchers call the scaling hypothesis: as models grow, performance reliably improves. At certain thresholds, entirely new capabilities appear—abilities not programmed in, but emerging from scale itself.

Training on Internet-Scale Data

Modern LLMs train on datasets that attempt to capture much of human-written knowledge. Books, news, Wikipedia, academic papers, forums, and billions of web pages all contribute. GPT-3 alone was trained on roughly 500 billion words—about a million novels’ worth of text.

Training at this scale introduces new challenges. Raw web data is messy: it contains spam, duplicate content, and harmful or low-quality material. Researchers must filter aggressively, while still keeping enough diversity to make models broadly capable. Striking the right balance between quantity and quality is an ongoing puzzle.

Another striking feature is diversity. These datasets span dozens of languages and cultural contexts, enabling cross-linguistic abilities and cultural awareness. That’s why LLMs can often translate, recognize slang, or understand references drawn from different parts of the world.

The Training Process at Scale

The training process, though conceptually simple, becomes a massive engineering effort. The goal remains to predict the next word. A model sees a phrase like “The capital of France is” and learns to continue with “Paris”. But scaling this objective requires extraordinary resources.

Training runs are distributed across thousands of processors, with billions of parameters spread across many machines. In the early stages, predictions are mostly random. With repeated passes through the data, the model gradually learns grammar, then vocabulary, then broader factual patterns. Over time, abilities like problem-solving and contextual reasoning begin to emerge.

This scale comes at a cost. Training the largest models can require millions of dollars in compute and enough energy to power thousands of homes for months. Engineers carefully monitor metrics throughout—loss reduction, gradient stability, emerging capabilities—to keep training on track.

Emergent Capabilities

One of the most fascinating aspects of LLMs is that simply making them bigger produces abilities that weren’t explicitly programmed. A smaller model can only mimic grammar and common word associations, but at scale, new skills begin to surface.

🤖 Few-Shot Learning Example:

- Show the model a handful of English–French translation pairs, and it can continue the pattern with new sentences.

- The same happens with reasoning tasks—after seeing a few examples, it can solve math problems or write small pieces of code without extra training.

Beyond this, large models integrate knowledge across fields. They can answer questions that combine history with science, or literature with philosophy. They also venture into creativity, writing poetry, inventing jokes, or generating stories that follow genre conventions. Perhaps most impressively, they can sustain extended dialogue, tracking context across multiple turns.

From Base Models to Conversational AI

The raw models that emerge from training are powerful, but they don’t yet behave like helpful assistants. By default, they just continue text, which isn’t always useful. To transform them into conversational systems, they go through extra training steps.

- Instruction tuning teaches them to follow explicit commands rather than drifting off in free association.

- Alignment training encourages them to be helpful, harmless, and honest, countering the biases and harmful content in internet text.

- Conversational fine-tuning exposes them to dialogue datasets, so they learn how to hold multi-turn conversations and ask clarifying questions.

- Human feedback plays a central role: trainers rank responses, guiding models toward outputs that people find most helpful.

Some organizations also fine-tune these models for specific tasks like education, customer service, or creative writing, tailoring them for particular domains.

The Architecture Behind Modern LLMs

Most modern LLMs use the Transformer architecture from Chapter 4, powered by the attention mechanisms we encountered earlier. At scale, this architecture becomes especially powerful.

Attention allows the model to decide which parts of the context matter most, and in large models this happens across very long sequences—sometimes thousands of words. Multi-head attention means different “heads” focus on different things simultaneously: grammar in one case, semantic links in another, long-range references in yet another.

The depth of these networks matters too. Dozens or even hundreds of stacked layers gradually build more abstract representations. Early layers capture grammar; later ones encode world knowledge and reasoning patterns. Together, billions of parameters distributed across these components make possible the capabilities we see in practice.

Capabilities and Limitations

LLMs can write coherently on almost any topic, answer factual questions, translate languages, generate code, and hold conversations that feel natural. They often perform these tasks at or above average human levels.

But limitations remain clear. At their core, LLMs are prediction engines, not reasoning systems. They sometimes produce fluent but incorrect answers—so-called hallucinations. Their knowledge is frozen at the point of training, leaving them blind to recent events. They can also be inconsistent: ask the same question in two different ways and you may get two different answers. And because they require enormous compute, access to the largest models is concentrated among a handful of well-resourced organizations.

The Social and Economic Impact

These systems are already reshaping how people work, learn, and create. Writers, programmers, and researchers use them as productivity tools for drafting, coding, and summarizing. Educators explore them as tutors and assistants, while also grappling with how they change assessment and academic integrity. Creative industries face both opportunities and disruptions as models generate stories, marketing copy, or design ideas.

The economic implications are significant. Tasks once considered safe from automation—summarizing documents, analyzing reports, answering customer queries—are increasingly handled by AI. At the same time, the spread of LLMs raises regulatory and ethical concerns: how to prevent bias, ensure safety, and govern systems with such broad reach.

👩🏻🏫 Bias Example: Remember when we talked about bias in the bias–variance tradeoff? There, bias meant a model’s tendency to make systematic errors because it’s too simple.

However, when we talk about bias in large language models, we usually mean social or cultural bias. For instance, an LLM trained on internet text might associate certain professions more strongly with one gender—e.g., generating “he is a doctor” and “she is a nurse”—even when prompted neutrally.

The Future of Large Language Models

The rapid progress of LLMs shows no sign of slowing. Researchers are exploring several directions:

- Scaling further: pushing parameters and data even higher, with new emergent abilities.

- Multimodal models: combining text with images, audio, and video for richer understanding.

- Efficiency: building smaller, cheaper models that rival the performance of giants.

- Specialization: fine-tuning for domains like medicine, law, or scientific research.

- Safety and alignment: ensuring powerful systems remain trustworthy and beneficial.

Together, these directions point toward a future where large language models become more capable, accessible, and aligned with human needs.

Final Takeaways

Large language models are the product of simple principles—predicting the next word—applied at massive scale. The result is a system with emergent abilities in reasoning, creativity, and conversation. But these same systems remain constrained by prediction, frozen knowledge, and inconsistency.

Their rise is already reshaping industries, education, and society. Understanding both their strengths and their limits is essential as we navigate a future where human–AI collaboration becomes part of everyday life.