Machine Learning might seem mysterious, but it follows a surprisingly systematic process. Unlike humans who learn through understanding and intuition, machines learn by mathematically adjusting their internal settings to make better predictions over time.

Think of it like tuning a guitar—you start with random string tensions, listen to how it sounds, then gradually adjust each string until you get the right notes. Machine learning works similarly: start with random mathematical settings, check how well they work, then gradually adjust until you get accurate predictions.

The entire learning process breaks down into four essential steps: converting real-world information into numbers, choosing the right type of mathematical function, training that function to minimize mistakes, and testing whether it works on new examples.

Step 1: Representing the World as Data

Before any learning can happen, we need to translate messy real-world information into clean numerical data that computers can process mathematically.

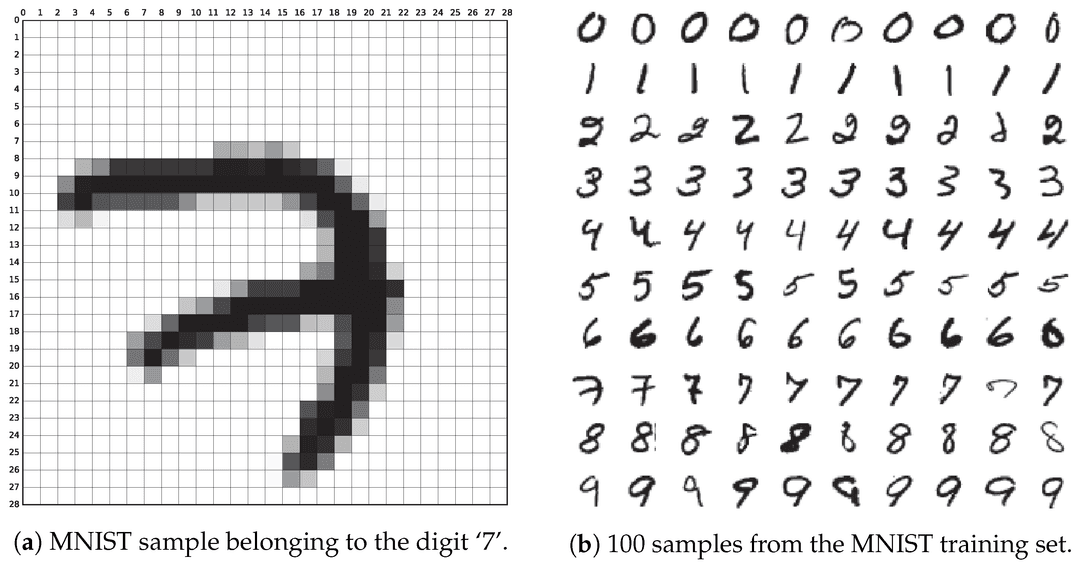

✏️ Handwritten Digit Recognition Example: One of the most famous examples in Machine Learning is recognizing handwritten digits from the MNIST dataset. While you can instantly see that a squiggly line represents a "7," computers don't see images the same way.

Instead, each pixel image becomes a matrix of 784 numbers, where each number represents how bright that pixel is (0 = black, 255 = white):

What looks like a simple "7" to us becomes a matrix like this:

Each row represents a part of the image, and these 784 numbers become the input for the machine learning model.

Different types of data have different manners of representation.

- Text: Words get converted to numerical codes or "embeddings" that capture meaning.

- Audio: Sound waves become sequences of frequency measurements.

- Financial data: Stock prices, trading volumes, and market indicators are already numbers.

- Medical data: Symptoms, test results, and measurements get standardized into numerical scales.

What about non-numerical categories like "spam," "promotion," or "inbox"? If we want to classify emails into multiple categories, we can’t input text labels directly. Instead, we represent them as numerical vectors:

| Label | Numerical Code |

|---|---|

| Spam | (1, 0, 0) |

| Promotions | (0, 1, 0) |

| Inbox | (0, 0, 1) |

Each category gets its own position in a vector, with a 1 marking the correct category and 0s everywhere else. This technique is called one-hot encoding. This way, we can transform categories into numbers that mathematical functions can work with.

Step 2: Choosing a Mathematical Function

Machine learning is fundamentally about finding the best function to map inputs to outputs:

- If is an email, could be spam or not spam.

- If is an image, could be a cat or dog.

- If is a house, could be its predicted price.

The key challenge is choosing what type of function to use. Different problems need different mathematical approaches.

🏠 Linear Function Example: Suppose we want to predict house prices based on size and location. We might start with a simple linear function, like we saw in Chapter 2, to model this:

In this function we have the following definitions:

- are called weights—they determine how much each input feature matters. We will see them more often.

- This is the bias—it gives a baseline prediction, like recognizing that a house will never sell for just €1.

- The goal is finding the right values for and .

And remember how we said is the input of the function? Here we essentially have split into two: size () and location (), both are input features. Therefore we could also write in a more mathematical way:

Now these so called weights are crucial in machine learning—they're like volume knobs that control how much influence each input has on the final prediction:

- If location matters more than size, will be larger than .

- If size barely matters, will be close to zero.

- Negative weights mean that feature pushes the prediction in the opposite direction.

Below are some variants to the weights and bias, look at how different perspectives might change the price calculating function:

Linear functions are the simplest way to model data. But once we move beyond them, things get complex fast—non-linear functions are more powerful, but also harder to train and understand. In the future, we may encounter other function types as well:

- Decision Trees: Use branching yes/no questions (like a flowchart).

- Neural Networks: Combine many simple functions to learn complex patterns.

The choice depends on your data and problem complexity. Simple problems might work well with linear functions, while complex problems like image recognition need more sophisticated approaches.

Step 3: Training the Function to Minimize Mistakes

Once we've chosen our function type, we need to train the model, essentially teaching it to make accurate predictions by showing it lots of examples. Notice that words like model, function, system are interchangeable here—they come down to the same core concepts.

The Training Loop:

- Start with random weights: The function begins making random predictions.

- Make predictions: Run training data through the current function.

- Calculate errors: Compare predictions to correct answers.

- Adjust weights: Use mathematical techniques to reduce errors.

- Repeat: Continue until predictions are accurate enough.

🐱 Cat Recognition Example: Let's say we're training a model to recognize cats in photos. In the first stage random weights mean the model guesses randomly—maybe 50% accuracy.

- After 100 examples: Slightly better than random—maybe 60% accuracy.

- After 1.000 examples: Starting to detect basic patterns—70% accuracy.

- After 10.000 examples: Reliably recognizing cat features—90% accuracy.

But how does an AI system know how to adjust the weights? This is where derivatives from Chapter 2 become essential! The system calculates how changing each weight would affect the error, then adjusts weights in the direction that reduces mistakes. We'll explore this gradient descent process in detail in later chapters.

For the house price example, if the model predicts €300.000 but the actual price is €250.000, the error is €50.000. The training process adjusts weights to make future predictions closer to actual values.

Step 4: Testing Generalization on New Data

The ultimate test of machine learning isn't how well it performs on training data—it's how well it handles completely new examples it has never seen before.

A good machine learning practice involves splitting your data:

- Training Data (70-80%): Used to adjust weights and learn patterns.

- Test Data (20-30%): Hidden during training, used only for final evaluation. The model has never seen this data and we can use it to test its capabilities.

Generalization Success: A well-trained model should recognize handwritten digits from different people's handwriting, detect spam emails even when spammers change their tactics, predict house prices in neighborhoods not included in training data, and identify cats in photos taken with different cameras, lighting, and angles.

Sometimes models cheat by memorizing training examples instead of learning real patterns:

- Good Learning: "Cat photos usually have triangular ears, whiskers, and fur textures".

- Bad Memorization:"Image #1247 in my training set is a cat".

The memorizing model fails on new cat photos because it never learned what actually makes something a cat—it just remembered specific training images.

This is why it's important to also have test data, it helps us asses the model. When a model achieves 99% accuracy on training data but only 60% on test data, it has memorized rather than learned. Good generalization shows similar performance on both training data (85%) and test data (83%), indicating the model learned transferable patterns.

Final Takeaways

Machine learning transforms the challenge of programming intelligent behavior into a systematic optimization process. By converting real-world data into numbers, choosing appropriate mathematical functions, training through iterative weight adjustment, and validating through generalization testing, machine learning systems learn to recognize patterns and make accurate predictions.

The key insight is that learning happens through mathematical optimization—gradually adjusting function parameters to minimize prediction errors—rather than through understanding or reasoning as humans do.