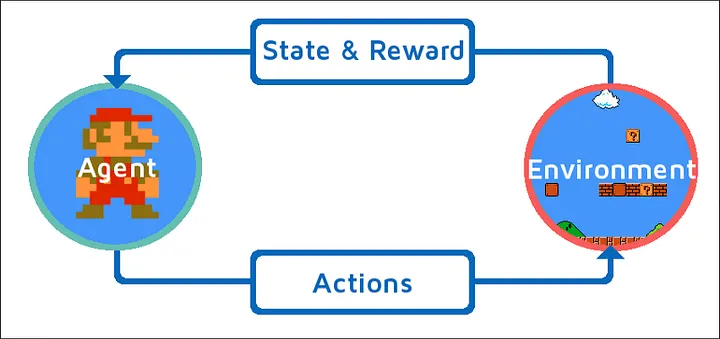

Every reinforcement learning system follows the same basic structure: an agent (the decision-maker) interacts with an environment (the world it’s trying to navigate or optimize). This framework is highly versatile, describing everything from trading algorithms and recommendation systems to game-playing AIs. In each case, the agent observes, decides, acts, and learns from the outcome.

The elegance lies in this simple cycle—repeated interactions provide feedback that continually shapes and improves the agent’s behavior.

The Agent: The Decision Maker

The agent is the AI system at the center of reinforcement learning—the entity that perceives, thinks, and acts. Unlike passive systems that simply process input and produce output, agents are active participants that make decisions with consequences.

Think of the agent as having several key responsibilities:

- Perception: The agent must understand its current situation by processing information from the environment. This might be the current state of a game board, sensor readings from a robot, or user behavior data in a recommendation system.

- Decision-making: Based on what it observes, the agent must choose what action to take next. These decisions start random but become increasingly sophisticated as learning progresses.

- Learning: After each action, the agent updates its understanding based on the results. This is where the "intelligence" develops—the gradual improvement in decision-making quality.

- Memory: The agent maintains knowledge about what strategies work well in different situations, building up experience that guides future choices.

The agent's sophistication can vary enormously. Simple agents might use basic rules or lookup tables, while advanced agents employ deep neural networks to process complex sensory input and make nuanced decisions.

The Environment: The World to Navigate

The environment encompasses everything outside the agent—the world it must understand, navigate, and influence. Environments can be physical (like a warehouse for a delivery robot), virtual (like a video game), or abstract (like a stock market or user preference space).

Environments have several important characteristics:

- State space: All the different situations the agent might encounter. In chess, this includes every possible board configuration.

- Dynamics: Some environments are predictable (chess rules never change), while others are stochastic (market prices fluctuate unpredictably).

- Observability: In some environments, agents can see everything (like chess). In others, information is partial or hidden (like poker or real-world navigation with limited sensors).

- Complexity: Environments range from simple (tic-tac-toe) to incredibly complex (managing a supply chain or understanding natural language conversations).

- Real-time constraints: Some environments demand immediate decisions, while others allow careful deliberation.

🚗 Autonomous Vehicle Example: For a self-driving car, the environment includes road conditions, weather, other vehicles, pedestrians, traffic signals, and countless other dynamic factors. The agent (driving system) must process sensor data to understand this environment and make driving decisions that safely reach the destination.

States: Snapshots of the World

A state represents a specific situation or configuration that the agent might encounter. States capture all the relevant information needed to make good decisions at any given moment.

The challenge in defining states is finding the right level of detail:

- Too simple: Miss important information that affects decision quality. A chess program that only considers piece counts but ignores positions would make poor moves.

- Too complex: Include irrelevant details that make learning harder and slower. A trading algorithm doesn't need to know the weather unless it's trading agricultural commodities.

- Just right: Capture the essential information that determines which actions are likely to succeed.

Different problems require different state representations:

- Games: Board positions, scores, remaining time.

- Robotics: Joint positions, sensor readings, obstacle locations.

- Finance: Price trends, market indicators, portfolio compositions.

- Recommendation: User history, item features, contextual information.

The quality of state representation significantly impacts learning success. Well-designed states help agents learn faster and make better decisions.

Actions: What the Agent Can Do

Actions represent the set of choices available to the agent at any given moment. The design of the action space—what actions are possible and how they're structured—profoundly influences how the agent learns and behaves.

Action spaces come in different forms:

- Discrete actions: A finite set of distinct choices, like chess moves or button presses in a video game. These are often easier to learn but may limit flexibility.

- Continuous actions: Actions defined by numerical values, like steering angles or bid amounts. These offer more precision but can be harder to learn effectively.

- Composite actions: Complex actions built from simpler components, like "go to the kitchen and make coffee" composed of many individual movements and decisions.

- Conditional actions: Actions that depend on the current state, like "if the price drops below X, then sell Y shares."

🎮 Game Example: In a racing game, the agent might have discrete actions (accelerate, brake, turn left, turn right) or continuous actions (steering angle from -1 to +1, throttle position from 0 to 1). The continuous approach offers more precise control but requires more sophisticated learning algorithms.

Rewards: The Learning Signal

Rewards are the feedback mechanism that drives learning in reinforcement learning systems. They tell the agent how well it's doing and provide the signal for improving future behavior.

Designing good reward systems is both crucial and challenging:

- Immediate rewards: Direct feedback for individual actions, like points for eating dots in Pac-Man or penalties for collisions in autonomous driving.

- Delayed rewards: Feedback that comes after a sequence of actions, like winning or losing a chess game. These are harder to learn from but often more meaningful.

- Sparse rewards: Situations where feedback is infrequent, like only getting a reward for completing an entire task. This makes learning more difficult but reflects many real-world scenarios.

- Dense rewards: Frequent feedback that guides learning more directly but requires careful design to avoid unintended behaviors.

💰 Trading Example: A trading algorithm might receive rewards based on profit, but this needs careful design. Rewarding only final profit might encourage excessive risk-taking. Rewarding frequent trades might lead to overtrading. The reward structure shapes the trading strategy that emerges.

Policies: The Agent's Strategy

A policy defines how an agent chooses actions in different situations. It's the agent's strategy or decision-making rule that maps from states to actions. As learning progresses, the policy evolves from random or simple rules toward sophisticated strategies.

Policies can take different forms:

- Deterministic policies: Always choose the same action in the same state. Simple and predictable but potentially limiting.

- Stochastic policies: Choose actions probabilistically, allowing for exploration and adaptation to changing conditions.

- Parameterized policies: Policies defined by adjustable parameters (like neural network weights) that can be optimized through learning.

The policy is what we ultimately care about—it represents the agent's learned behavior and determines how well it performs in the environment.

Putting It All Together

These components work together in a continuous cycle that drives learning and improvement:

- State observation: The agent perceives the current state of the environment

- Action selection: Using its current policy, the agent chooses an action

- Environment response: The environment transitions to a new state and provides a reward

- Policy update: The agent uses this experience to improve its policy

- Cycle repetition: The process continues with the new state

This framework applies regardless of the specific problem domain. Whether training a robot to walk, optimizing ad placements, or developing game strategies, the same basic structure guides the learning process.

The power comes from the framework's generality—once you understand these components, you can recognize how reinforcement learning applies to countless different problems and domains.

Final Takeaways

The agent-environment framework provides the conceptual foundation for all reinforcement learning systems. By understanding how agents observe states, choose actions, receive rewards, and update policies, you can see how intelligent behavior emerges from simple interactions.

This framework's versatility explains why reinforcement learning has found applications across such diverse domains—from robotics and game-playing to finance and recommendation systems. The same basic structure adapts to radically different environments while maintaining the core learning principles.