Training deep neural networks sounds straightforward in theory: define a network architecture, feed it data, run backpropagation and gradient descent, then wait for good results. In practice, Deep Learning is far more challenging. Networks can memorize instead of learn, gradients can vanish or explode, and finding the right hyperparameters often requires extensive experimentation.

These challenges explain why deep learning is still as much art as science, and why experienced practitioners develop intuition through years of trial and error. Understanding these common pitfalls helps explain why training state-of-the-art models can take weeks or months, require specialized hardware, and demand careful monitoring throughout the process.

Overfitting: When Models Memorize Instead of Learn

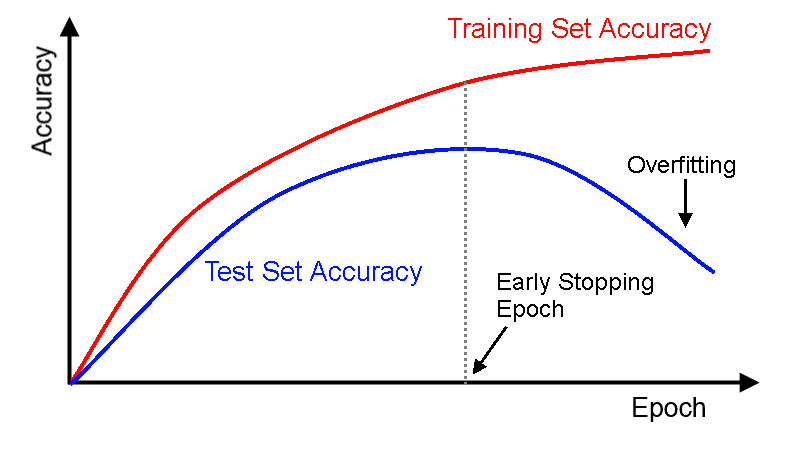

Overfitting is perhaps the most common problem in deep learning. It occurs when a model becomes too specialized to its training data, learning specific examples rather than general patterns that transfer to new situations.

🐱 Cat Recognition Example: A network training on cat photos might learn that "images with trees in the background are cats" if many training photos happen to show cats near trees. When it later encounters a photo of a dog near a tree, it confidently (and incorrectly) predicts "cat."

From a mathematical perspective, overfitting happens when a model has too much capacity relative to the amount of training data. With millions of parameters, deep networks can potentially memorize every training example instead of learning underlying patterns:

- Training accuracy continues improving while validation accuracy plateaus or decreases.

- Large gap between training and validation performance.

- Model makes confident predictions on examples very different from training data.

Solutions to Overfitting

Luckily there are some techniques to prevent overfitting.

More Data: The most effective solution, though often the most expensive. More diverse training examples help models learn general patterns rather than specific quirks.

Regularization: Mathematical techniques that penalize model complexity. For example encouraging sparse weights (many weights become zero), or encouraging small weights, preventing any single feature from dominating

Dropout: During training, randomly "turn off" some neurons in each layer. This forces the network to learn robust features that don't depend on specific neurons, similar to how studying with different groups of friends makes you more well-rounded.

Early Stopping: Monitor validation performance and stop training when it begins to deteriorate, even if training performance continues improving.

Underfitting: When Models Are Too Simple

The opposite problem occurs when models lack sufficient capacity to capture important patterns in the data. This is like trying to fit a curved relationship with a straight line—the model is fundamentally too simple for the task. Underfitting has some common causes:

- Insufficient model complexity: Too few layers or neurons.

- Inadequate training: Stopping before the model converges.

- Poor learning rate: Too low, preventing effective weight updates.

- Over-regularization: Penalties so strong they prevent learning.

Just like overfitting, we can recognize underfitting by a number of ways:

- Both training and validation accuracy remain low.

- Loss plateaus at a high value early in training.

- Model predictions seem overly simplistic or random.

Solutions to Underfitting

Underfitting can be solved using some of these techniques:

- **Increase model capacity: Add layers, neurons, or parameters.

- Train longer: Allow more epochs for convergence.

- Adjust hyperparameters: Tweak learning rate.

- Feature engineering: Provide better input representations.

Remember the bias-variance trade-off from Machine Learning? Overfitting and underfitting represent opposite ends of the bias-variance spectrum. The art of deep learning lies in finding the sweet spot between these extremes.

The Loss landscape

To understand why deep learning is so challenging, we need to visualize what gradient descent is actually trying to accomplish. Training a neural network means finding the best possible weights among billions of possibilities—like finding the lowest point in a vast, complex landscape while blindfolded.

The algorithm sounds simple: compute gradients, take steps downhill, repeat until you reach the bottom. Which is easy to do for simple functions like out lemonade stand example back in Chapter 2. But the "landscape" that gradient descent must navigate in deep learning is extraordinarily complex. Take a look at these representations of loss landscapes:

Challenging Terrain Features

Real loss landscapes exist in spaces with millions or billions of dimensions, making visualization and intuition extremely difficult. This also brings some difficult terrain features to overcome:

Local Minima: Points that appear optimal from nearby but aren't the global best. Imagine being in a small valley, surrounded by hills, unaware that a much deeper valley exists beyond your view.

Saddle Points: Points that slope down in some directions and up in others, like mountain passes. These can trap gradient descent because gradients are near zero, but they're not true minima.

Plateaus: Flat regions where gradients are tiny, causing learning to slow dramatically. The model might spend thousands of iterations making minimal progress.

Sharp Cliffs: Regions where gradients change rapidly, potentially causing gradient descent to overshoot and become unstable.

Vanishing Gradients: When Deep Networks Stop Learning

As networks become deeper, a fundamental mathematical problem emerges: gradients can become exponentially smaller as they propagate backward through layers.

During backpropagation, gradients are computed using the chain rule, multiplying derivatives across layers. When activation functions are used, these derivatives are often less than 1. Multiplying many small numbers together produces extremely small results.

Take a look at the following example of a gradient flowing backward:

- Layer 10: .

- Layer 9: .

- Layer 8: .

- Layer 7: .

- ...

- Layer 1:

By the time gradients reach early layers, they're so small that weight updates are negligible. This can have some big consequences:

- Early layers learn very slowly or stop learning entirely.

- Networks take extremely long to train.

- Deep architectures perform no better than shallow ones.

Solutions to Vanishing Gradients

Picking the Right Activation Functions: ReLU has a derivative of 1 for positive inputs, preventing gradient shrinkage.

Better Weight Initialization: Careful initialization prevents gradients from vanishing from the start. For example by scaling weights based on layer size or starting at a favourable position for you activation function.

Residual Connections: Skip connections allow gradients to flow directly across layers, bypassing potential vanishing points. This is the key innovation in ResNet architectures.

Batch Normalization: Normalizes layer inputs to maintain stable gradient flow throughout training.

Computational and Practical Challenges

Beyond mathematical difficulties, deep learning faces significant practical obstacles, such as:

Computational Requirements:

- Training time: State-of-the-art models can require weeks of training on powerful hardware.

- Memory usage: Large models may not fit on standard GPUs, requiring specialized infrastructure.

- Energy consumption: Training large models can consume as much electricity as a car over its lifetime.

Hardware Dependencies:

- GPU/TPU requirements: Training deep networks on CPUs is often impractical.

- Memory limitations: Larger models require more expensive hardware.

- Distributed training: Very large models require multiple machines working together.

These practical constraints underscore that advances in deep learning depend not only on better algorithms, but also on the availability of powerful and efficient hardware.

Why These Challenges Matter

Understanding these difficulties helps explain several important aspects of modern AI.

- AI research takes time, each breakthrough requires overcoming fundamental mathematical and computational obstacles, not just algorithmic improvements.

- Models are expensive, the computational requirements for training and running large models create significant infrastructure costs.

- Progress is incremental, each improvement in architectures, optimization techniques, or hardware enables slightly more complex problems to be solved.

Recognizing these challenges highlights why deep learning advances are hard-won and why each step forward represents a significant achievement in AI.

Final Takeaways

Training deep neural networks involves navigating mathematical, computational, and practical challenges. Overfitting and underfitting reflect the trade-off between model complexity and generalization. The loss landscape is filled with local minima, saddle points, and plateaus that can trap or slow gradient descent. Vanishing and exploding gradients complicate deeper architectures, requiring solutions such as ReLU activations, careful initialization, and new network designs.

On top of this, large computational requirements and hyperparameter sensitivity make training both expensive and demanding. These obstacles explain why deep learning success relies not only on theory but also on practical experience, resources, and persistence—and why each breakthrough represents a hard-won advance.